I recently learned about the historic phenomenon of the Year Without a Summer, a global cooling event in 1816, when a volcanic ash cloud covered the skies over Europe for much of the year. In the words of Lord Byron,

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless; and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day.

Whether it’s the year without summer, Berlin’s perpetually ashen skies or Operation: Dark Storm in The Matrix, I’ve long been fascinated by the image of the obstructed Sun. I first became aware of this fascination at the age of nine, on the day of the full solar eclipse, when, in the span of 12 hours, I ate an entire 9-kilogram watermelon. As a 10-year-old, I considered this a fiendish achievement. Watermelon was my favourite fruit, and indulging in it on the day the Sun ghosted Serbia felt like an act of cosmic defiance, an attempt to eat summer back into existence.

There was a time in Earth’s prehistory, long before humans were around, when the Sun was only 70% the strength of the Sun we know today. A time when life relied on geochemical processes and had no eyes or a complex enough nervous system to loop around itself and develop a subjective perspective. A time without sight, summer and auto fiction.

I have very few episodic memories from my childhood outside moments of crisis or cosmic events. The postwar recession, the NATO bombings, the solar eclipse, 9/11, the deaths of loved ones, heartbreaks—these were times in my life when I felt most present. Much like meditating on the planet’s prehistory, experiencing life-altering events somehow provided a substrate for embedding my memories and supporting their long-term persistence.

I guess if there are really 2 types of reactions to the world ending like how Lars von Trier depicts it in Melancholia, I clearly belong to the Justine category. My therapist would say that this is internalised numbing, a survival mechanism I developed to protect myself as a child. But I prefer to believe that there is something more universal, something objectively grounding about experiencing the world at the brink of collapse. After all, unless it is an actual asteroid hitting the earth like in Melancholia, most crisis scenarios, even if they entail the end of one world, do not entail the end of subjective experience. The end of subjective experience (death) is literally outside of experience, hence in a way, when one is in the position of the observer, one gets to experience eternity. And the more worlds are born and end within this eternity, the more one learns to feel present.

In the sunless summer of 1816, amidst storms on the shores of Lake Geneva and in the company of Lord Byron and other artistic luminaries, Mary Shelley gave shape to the story of Frankenstein.

In ancient cultures, monsters embodied the cosmic liminal, representing a world governed by forces greater than humankind. In the Promethean myth, the ancient precursor to Shelley’s tale, it is humanity itself that appears as the “creature,” fashioned from clay and animated by stolen fire. While ancient monsters were mythic, otherworldly and larger than life, modern monsters became increasingly human and relatable: we feel pity for Frankenstein’s creature, recognize its pain, while we contemplate Frankenstein’s ambition and hubris. The monsters of our contemporary era are neither cosmic, nor moral or humanistic, but instead formless, opaque and shapeshifting. They crawl under our skins (literally), inhabit our bodies and contaminate our brains.

As J.J. Cohen reminds us, “the monster always escapes,” only to resurface in different forms at different times. Monsters are signs of a healthy cultural body: they represent threats that we externalise in order to be able to face them.

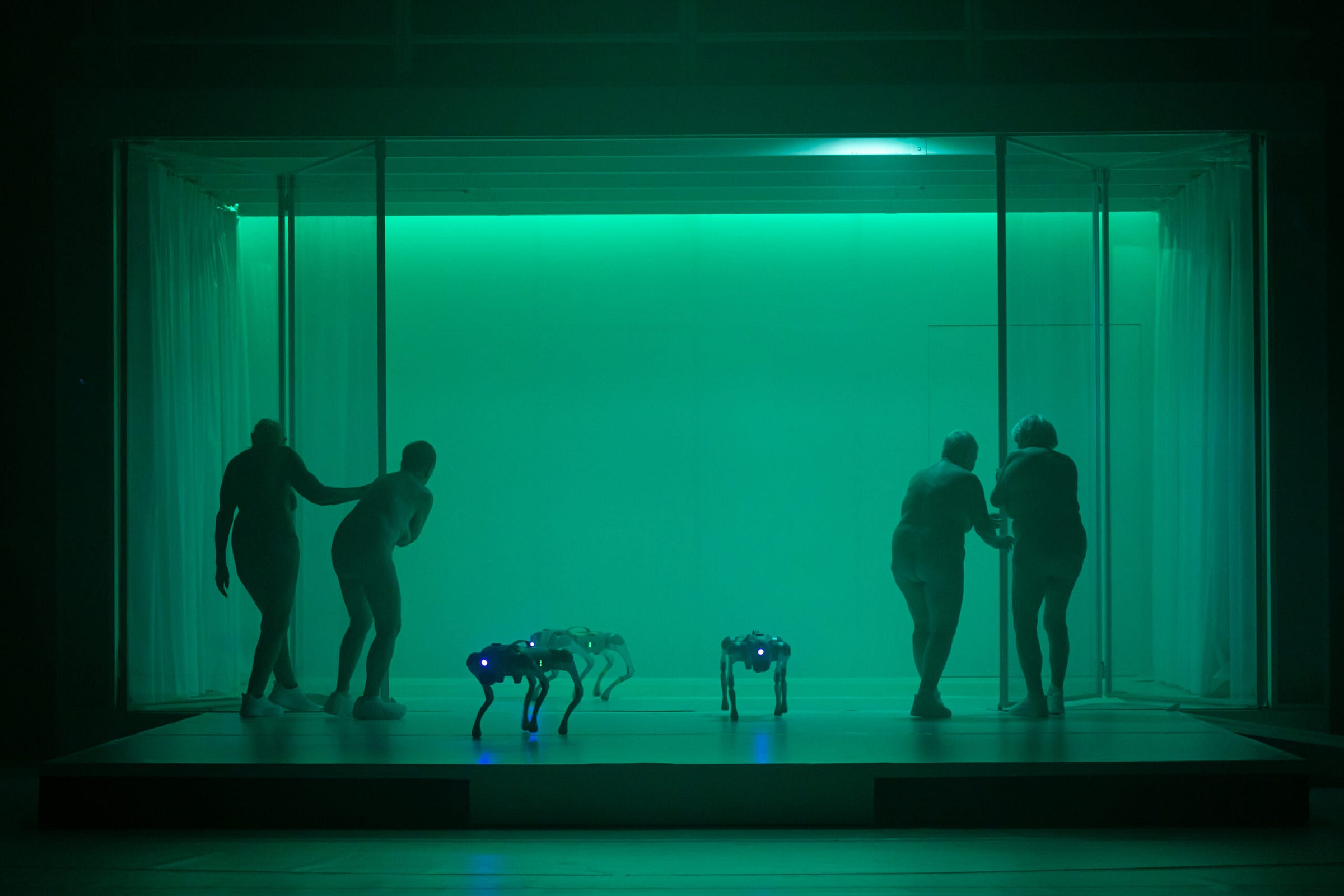

Whether due to a pervasive sense of Western cultural decline, the mounting weight of war and climate catastrophe, or simply the incessant yapping of AI doomers, we are witnessing a resurgence of the monster genre, and several recent and upcoming blockbusters are in explicit dialogue with Shelley’s Frankenstein: Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things, as well as the forthcoming adaptations by Guillermo del Toro and Maggie Gyllenhaal. This return to Frankensteinian motifs is not confined to cinema: Florentina Holzinger’s latest theatre piece, Year Without Summer, also features a Frankenstein figure and opens with the historic image of the climate catastrophe that foreshadowed Shelley’s writing.

From the outset, Year Without Summer fuses planetary catastrophe, autofictional confessions, and abject body horror. Whether suspending performers from steel hooks pierced through their flesh or burying a miniature glass embryo in an open wound, Holzinger’s imagery is beyond visceral, almost directly neural. Rejecting formalism, institutional codes, and aesthetic purism, she is drawing on Julia Kristeva’s concept of the abject: that which is expelled, excluded, cast out to secure the boundaries of the self. For Kristeva, the abject invokes the primal rupture that founds subjectivity itself: the infant’s separation from oneness with their primary caregiver.

Confronting the abject recalls this primal separation, evoking both repulsion, as a threat to the integrity of the subject, and longing, for the lost unity with the pre-symbolic, intensive whole.

The abject materialises in substances like the white, creamy, waxy or oozy coating on a newborn’s skin, the placenta, and the literal waste products of the body like nails, skin, hair, feces. Today however, the abject in cinema is in increasingly less about body horror, and more about the horror of the impossibility of a coherent “I.”

This signals a new kind of trauma: in a world where thinking and speaking are no longer exclusive to organic beings, we turn to horror simply to feel like an “I”. After all, the greatest monster of our time, AI, is disembodied, distributed, and speaks in tongues. It infiltrates our minds, quite literally, through brain-computer interfaces, much like FloHo’s hooks pierce performers’ flesh, or the spores that contaminate human bodies in Annihilation and The Last of Us.

The real threat however isn’t pain or death, but the fear that once a massive titanium hook penetrates our skin, we realise we don’t feel a thing anymore. Our subjective experience has continued uninterrupted as, without noticing, we transformed into something other than ourselves: a machine, a zombie, something inhuman; suspended, still processing information, but not quite alive.

In ancient times, the ineffable, or pure being, was considered part of reality: there was a reality presumed to materially exist beyond what words could express. While the Enlightenment relegated the ineffable to an epistemological limit, it resurfaced with Gödel as the residue of formal systems. Today, the circle has been closed: life is increasingly defined through cybernetics, information theory, and biosemiotics. And if processes, signals, and their meaning are what it means to be alive, death is no longer an ontological event but literally a point where we stop doing things in the world that make sense.

At the end of Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó, a movie about a collapsing Hungarian village, the doctor, having returned from the hospital, boards up his window entirely, cutting out all light and sealing himself in darkness. He then sits at his desk and begins writing the same lines that opened the film, closing the loop on the narrative. Meanwhile, distant church bells continue to toll, bells that have marked the passage of time throughout the film with mechanical indifference, as if tolling not for any event but merely to remind the living that time moves on, heedless of their despair.

If traditional apocalypse offers revelation or judgment, Sátántangó’s apocalypse is a final sealing-off of meaning, when repetition no longer reveals semantic difference, and life ceases to perpetuate itself. Death becomes a hall of mirrors, where existence is validated only by its appearance to thought, and thought itself spins endlessly within its own abstractions, leading to entropic collapse: a world where nothing new can emerge because nothing is permitted to exist outside the recursive circuits of perception and signification.

The villagers’ stasis, the mud-choked landscapes, and the interminable pacing all point to a kind of metaphysical exhaustion, where life is no longer lived, only indexed. In this vision, apocalypse is not a singular event but an ongoing condition: the slow suffocation of the world by thought. Holzinger’s Year Without Summer offers equally no resolution. In its final image, humans continue shovelling shit amid climate collapse, yet there is always another dance to dance.

Anna Kornbluh shuns this style of aesthetic expression in her book Immediacy, the Style of Too Late Capitalism. She juxtaposes construction with expression, claiming that contemporary art is no longer symbolically constructed, but intuitively expressed. One of her prime examples are auto fiction and the first-person turn in contemporary literature, calling it a “formless form” in which the novel’s structure dissolves into fragments of self-narration.

What she overlooks, however, is that first-person narration paradoxically does more than create immediacy: by inviting the reader into an unfamiliar subjective perspective, they reveal the mutability of the “I,” making the constructed nature of subjectivity not less but more explicit.

The process of making the form more formless—deterritorialisation, base materialism, grotesque realism, Foucault’s concept of the abnormal, the body without organs—all point to the liberatory potential of formlessness, as opposed to disimmediation. Bataille’s notion of l’informe, already in the 1930s, denoted not merely an absence of structure but an operation that undoes form: a gesture of declassification that pulls cultural production down from the pedestal of ideality and coherence. What for Bataille was a deliberate undoing of hierarchy becomes, in Kornbluh’s diagnosis, an uncritical acquiescence to the collapse of symbolic scaffolding.

While Victor Frankenstein was the ultimate auteur of the Enlightenment era, meticulously assembling his creature from materials sourced from the dissecting room, slaughter- and charnel-houses, late capitalism replaces individual authorship with market-demand-driven assemblages: films and games stitched together from popular micro genres and images generated based on keyword lists optimized by ChatGPT for maximum attention.

The abject of contemporary AI no longer represents the attempt at defining subjectivity by confronting the non-subject (abject residue) ala Kristeva, instead it represents the subject attempting to redefine itself from the inside: through facing the clusters of flows & tendencies it is continuously reduced to. AI monsters morph and mutate in public spaces, always near you, soon maybe next to you, looming behind your back, reminding you that you’re continuously being tracked and aggregated into sellable user targeting attributes.

Amid the deluge of engagement-driven slop aesthetics, the universe of brain rot memes is rapidly expanding. Unlike AI slop—assembled through tendencies optimized for the algorithmic gaze—brain rot represents the human-authored absurd: a confrontation between the human search for meaning and the indifference (or silence) of the universe.

Yet brain rot does seem to elicit a reaction from the universe, in the form of virality. We feel increasingly compelled to recognize and reshare content that isn’t explicitly optimized for capture, thus confounding the algorithm with the residue of human surplus that resist compression into tradable user profiles. Where AI slop smooths and sanitizes, brain rot offers the digital equivalent of glossolalia: unruly, affective, and perversely communal.

If every medium produces its own kind of subject, what sort of subject are brain rot and abject slop giving rise to? Lacan, extending Freud, conceptualized the subject across three interlocking registers:

The Symbolic (the Big Other): the register of language, law, and social structures, the site from which the subject “speaks.” The Matrix, essentially.

The Imaginary: the realm of images and identifications; the conscious ego formed when the infant first recognizes itself as an “I.”

The Real: that which resists symbolization; what lies outside language and representation—trauma, rupture, impossibility.

While Lacan offered a psychoanalytic account of what it means to act as individuals within the rules of the symbolic social order, developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello proposed a concept that offers a potentially complementary perspective to the Lacanian Big Other: shared intentionality.

According to Tomasello, the foundation of shared intentionality, what he calls joint intentionality, emerges in humans around nine months of age. At this stage, infants begin to point or direct their gaze not merely for instrumental purposes (e.g., “I want that ball”) but declaratively, looking at their play partners instead of the object itself to communicate shared awareness (e.g., “Look, we’re playing!” or “Why did you stop rolling the ball?”). This marks a fundamental cognitive shift: the child is no longer merely navigating the world in the presence of others, but is actively constructing a shared perspective with them.

Such declarative gestures reveal an emerging capacity in infants for joint attention and perspectival coordination, the foundational cognitive infrastructure for shared norms, mutual understanding, and collective meaning-making. For Tomasello, these abilities are what set human cognition apart from that of even our closest primate relatives. It is this early emergence of “we-intentionality” that scaffolds the later development of shared cultural practices, social norms, and institutional forms.

I can summon this sensation right now by conjuring the experience of watching a movie with a friend, a lover, or a group. A sappy scene that stirs emotion can feel like being stripped naked, not because of what is on the screen (I would not feel exposed if watching movie alone), but because I implicitly sense a shift in the room’s affective plane: The Big Other of the joint activity is making me blush.

In this sense, there is a register of human experience that is not necessarily mediated by symbols or representations, but by a pre-representational, affective plane. Kornbluh fails to recognise this affective plane as a potential site for collective action, yet the recent rise of populism and right-wing authoritarian leaders attests to its political potency. Political leaders are increasingly being elected based on the desires they are able to stir, instead of agendas they promote.

Much like emotions and affect were evolved as a metabolic budgeting system, we now regulate culture through compressed affects and percepts instead of symbols. This new, Latent Big Other is very different from the Big Other Anna Kornbluh wants to summon back. The new Big Other is above all flattening, transforms high-dimensional, structured input data into lower-dimensional, abstract vectors. It embeds both Mozart and Ballerina Cappuccina into points of the same space, and enables interpolation between them: the generation of instances that are continuous hybrids of the two.

Monsters of the Symbolic, institutional Big Other were themselves symbolic: they had to represent an idea through metaphor or allegory once that idea had already been formulated by culture. The monsters of the Latent Big Other are unactualized potentialities: the embryonic egg that doesn’t develop into a “normal” specimen but instead mutates into an anomaly, a hybrid, a category error—Monstro Elisasue of the Substance, or the chaotic renderings of AI slop.

Institutional mediation is predicated on canon formation—the circulation of ideas already stratified into discursive practices. Latent mediation, by contrast, allows a work to go viral before it enters the discursive plane and it increasingly feels like the discourse is merely playing catch-up with the vibes.

Historically, monsters were harbingers of category crisis; today, they represent the increasing impossibility of the category of the self. No longer emerging from the symbolic surreal of the individual unconscious, contemporary monsters are generated by the latent assemblages of dividuals, markets, and AI. They no longer stabilise a subject transcendent to experience, but preempt one that is immanently produced through contexts the sensing, affective body chooses to engage in.

This leads to a “subjective categorisation crisis” where culture is no longer produced through a traceable, dialectical process of thesis-anti-thesis-synthesis played out on the symbolic plane but instead “breaks out of” the affective plane through a phase-change like process. When the process of individuation goes wrong, we get Area X’s uncanny hybrids: the bear with an ursine body and human skull who screams with the voice of a dying woman or the human-shaped plant growths of vines or fungus. These creations are not simply grotesque, destabilising the human form but reflect a deeper ontological erosion, a gradual erosion of necessity of anything other than contingency itself.

Lacan’s concept of the Big Other needs a revision, not just to account for the shift from the symbolic to the latent plane of collectivity, but also to transcend the superstructure of market and AI with a cosmic sense of agency that would enable us to reimagine the process of individuation (change) beyond the limits of anthropocentrism.

As G. C. Spivak writes:

To be human is to be intended toward the other... the planet is in the species of alterity; belonging to another system; and yet we inhabit it... to think the planetary, rather than the global, is to prepare for ethical singularities without abstract universalism.

Spivak articulates the need for an ethics grounded in alterity, as a way to rethink the Big Other beyond the hegemony of the transcendent symbol. But if we are to avoid being trapped in the hall of mirrors of correlationism—the notion that we can access only the relation between thought and being, never being-in-itself—we must also reclaim a sense of the universal absolute. Not a universal that flattens difference in the name of sameness, but one that affirms alterity as constitutive of the universal itself.

Quentin Meillassoux’s response to the need for a universal absolute is the challenging and counterintuitive claim that everything could be otherwise. This absolute contingency becomes the new ground for abstraction, a non-nihilistic affirmation of the world that requires no recourse to pre-given values or divine guarantees. We can know that the absolute exists, and it is precisely the contingency of all things.

This does not necessitate nihilistic surrender, but rather opens a rational space for eventual truths, truths that are not yet actual, but entirely thinkable.

From this speculative premise emerges a new mode of subjectivity: the eschatological subject. Recognising the absolute contingency of being, this subject orients herself toward a radically different future, a world in which justice, though currently foreclosed, becomes contingently thinkable.

Tralalero Tralala, (AI) monsters, solar eclipses, the image of the faint young sun help us relate to this feeling of “everything could be otherwise.” Most religious traditions have some semblance of a death meditation—some for the sake of cultivating detachment from the self, others to remind us of heaven that we’ll enter if we don’t wear mixed fabrics or touch a woman on her period. Our death meditation in some twisted sense is scrolling the feed.

Auto fiction, (AI) monsters, brain rot lore, music that upends our sense of time expose this possibility by providing us with experiences of worlds beginning and ending from the vantage point of an un-dead observer. In this way, change is no longer predicated on the existence of a beginning and an end to a story; instead, it becomes realisable within the continuity of a 1st person perspective.

The realisation that everything is absolutely subject to being otherwise—any law, being, or cause—undermines fatalism and reveals that what we take as inevitable can always be challenged and changed, including capitalism, patriarchy, and essentialist forms of rationalism. AI monsters aestheticise this promise: as we see beings morph and transpire on our social media feeds in a never-ending dance of intensive mutation, we get a glimpse of a reality where everything goes and anything could be otherwise. AI monsters, even if in a very primitive way, help make the possibility of radically new futures more thinkable, thus, a utopia more viable.

Share this post