Thoughts on Agency From Inside the Intensity Machine

By a design researcher turned product manager who is (still) emotionally attached to technology

I often hear VCs, analysts and even colleagues talking about the market as if it was not a reflection of what is happening on the ground, but almost like a sentient force sensing and dictating what is going to be built next.

I believe that, for a number of reasons—one of them being the VC model and the other the echo chamber of Silicon Valley—the tech industry has tipped over an inflection point where, instead of a genuine interest in innovation, the perpetuation of its own generative model has become its primary driving force. As a product manager working in the AI space, I witness the effects of this increasing mechanisation of value generation in my work on a daily basis.

In the following essay, I will present a personal account of what I perceive to be missing in the ways we develop technology in the tech industry today. As my aim here is not education but provocation, I will make sure to attribute my sources rigorously, but I will leave some of my concepts borrowed from various disciplines unpacked.

I.

I love technology. I still do, despite having worked in the tech industry for over a decade now. I strongly believe that building technology collectively can be a transformative experience, if only we contended with the fact that value is collectively discovered, not automatically generated; stopped throwing entire companies at validating singular ideas; and instead started integrating methods of exploratory research deeper into the fabric of tech product development.

Traditionally, academia was the field reserved for exploratory research, and industry where scientifically validated ideas were exploited and scaled. However, for the first time in the history of technology, with the advent of LLMs, a paradigm-shifting technology has emerged not from the realms of publicly funded research labs, but from the private sector. And while the tech discourse is deeply occupied by debates over concepts like AGI, world models, alignment, and existential risks, few talk about the remarkable fact that we are witnessing the single biggest transformation in the field of human-computer interaction: the birth of the natural language interface. Because of this, and because I really think machine learning is will be could be awesome, I believe these times in tech will retroactively be labelled as revolutionary.

According to one of the OG figures of history of science Thomas Kuhn, science has alternating ‘normal’ and ‘revolutionary’ (or ‘extraordinary’) phases. The revolutionary phases occur before paradigm shifting theories become the new norm in science. Revolutionary technology (ala Kuhn’s revolutionary science) does not merely mean accelerated progress but has several traits that qualitatively set it apart from technology built in legacy paradigms. Revolutionary periods require extraordinary research, characterised by:

a higher level of flexibility to create and integrate new concepts

a higher degree of interdisciplinary collaboration

a LOT of reflexive analysis in the form of speculation and critique.

In Kuhn’s words:

The proliferation of competing articulations, the willingness to try anything, the expression of explicit discontent, the recourse to philosophy and to debate over fundamentals, all these are symptoms of a transition from normal to extraordinary research. It is upon their existence more than upon that of revolutions that the notion of normal science depends.

- 'The Structure of Scientific Revolutions' by Thomas S. Kuhn.

In contrast,

move fast and break things

fail fast, fail cheap

ramp up intensity

are what countless startup books cite as keys to entrepreneurial success.

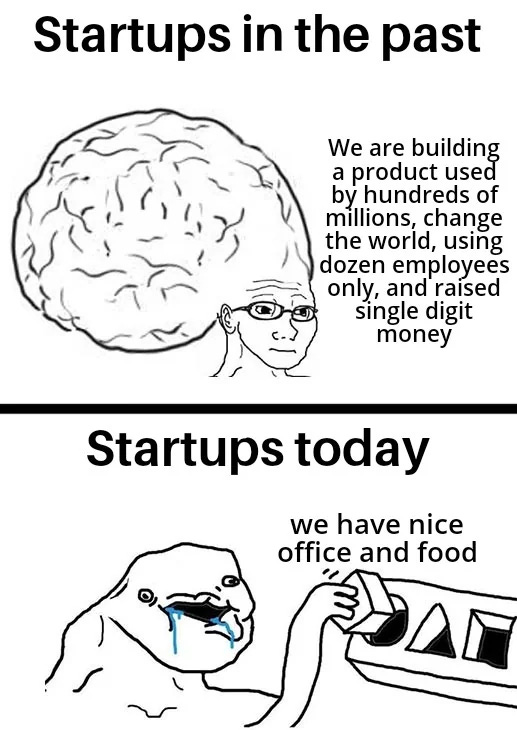

While the first VC funded startups were built around a strong core vision and were driven by a deep seated belief in the vision’s potential to generate value, contemporary startups are often governed by processes reminiscent of natural selection, ramping up intensity just to accelerate random mutation and find out what ideas ‘get selected’ under prevailing market conditions. Investors are more likely to fund ideas that have the potential to grow and scale, often at the expense of profitability in the early stages. It’s less about believing that the idea has the potential to make a difference in the world and more about using signals from the market to shape the idea according to what has the most potential for growth.

This dynamic is also reflected in

VC logic itself: VCs invest in a portfolio of startups, well aware that a high percentage of them will fail, but also expecting that the successes will yield substantial returns. Encouraging startups to fail fast and cheap mitigates the downside risk of each investment, allowing VCs to allocate resources more efficiently across their portfolio and make more $$.

engineering culture

I personally thrive in intensive environments and can see how ramping up intensity creates better-performing machines. Counterintuitively, the more I have on my to-do list, the more I can achieve in a day beyond it. As a product manager, I talk to customers, answer Slack messages, participate in meetings, write up Notion pages, which all make me feel like I am advancing something bigger than myself; I’m in direct service of the ‘intensity machine’. However, if I was only talking to customers, answering Slack messages, showing up at meetings, writing up Notion pages, I would be a terrible PM.

Prior to transitioning to product management I worked as a UX researcher, and a significant portion of my workday was dedicated to analysis and reflection. The name of my research studio, Reflexive Codes, is actually inspired by Grounded Theory, a qualitative research methodology that constructs knowledge from the bottom up through abductive reasoning.

Doing research in line with Grounded Theory involves annotating empirical data with “codes” and then using these codes to construct higher-level categories, thereby deriving meaning by advancing through increasing levels of abstraction. It's a research method that functions almost inversely compared to traditional research methods: instead of starting with a hypothesis (clearly defined problem), the researcher begins with an area of study and allows the hypotheses to emerge from the data.

As I transitioned to being a PM, I realised that most roles outside of UX research do not explicitly practise this type of abductive meaning-making process. Engineers' mode of operation is often confined to solutionizing, or solving well-defined problems, while designers focus their efforts on the same problems, but from the perspective of user experience. I quickly understood that as a PM, the reductive term 'prioritisation' means that I will have to delineate problem spaces and create concepts without dedicated time for analysis, reflection, much less collective speculation and critique.

In my day-to-day work, I had to learn to hone my skills of doing analysis on the fly, through being in dialogue with others. And while learning through dialogue is a valuable way to move and think together with the collective intelligence of the company, if everyone tasked with problem discovery just talked but no one reflected, that collective would end up being just that—a collective, without much added intelligence.

Industry teams have been optimising for decades to leverage what I call 'swarm intelligence' in product development: teams of individuals with limited agency interacting with each other based on simple principles. It's a form of collaboration that is well suited for incremental/cumulative development, a mode of operation predominant in established technological paradigms, but, as I will argue, inadequate during periods of revolutionary technological change.

II.

Technological progress, in the last couple of decades, has become synonymous with the incremental betterment of consumer products—innovation not as the outcome of deliberate imagination but as the compound result of automated, subconscious decision-making.

Around the middle of the 20th century, as a direct result of the trauma induced by totalitarian regimes and the impending nuclear-war, cold-war era scientists began to question humans’ ability to make reliable decisions. While the enlightenment-era mind was capable of objectivity, planning and predicting the future, the new model of the mind became distributed, stochastic and unable to plan reliably.

This particular ideology of networked intelligence has not only inspired the creation of the first neural nets but also our current economic system:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form, but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate "given" resources—if "given" is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these "data." It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilisation of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality.

-Friedrich Hayek, "The Use of Knowledge in Society," The American Economic Review XXXV, no. September (1945): 519-20. via Orit Halpern’s talk at ICI Berlin.

Since 1945, this idea has morphed into an ideology suggesting that just because one person cannot possibly grasp all the complexities of the world–unlike Leibniz, Goethe, or whoever was the last person to have read all the books that existed in their time–one shouldn’t even attempt to understand the world in its totality.

I often catch myself embodying the ideology of networked intelligence by relying too much on my subconscious cognition. I show up at work, turn on my autopilot and start ‘providing value’ by a flip of a button. I can lift my hands off the wheel and my “tacit, practitioner’s knowledge” will take care of the rest. And while unconscious cognition has tremendous powers, it is truly understudied and it saved my ass countless times in life, I still prefer to live my life examined, at least with the intention of keeping my hands on the wheel.

I am also a big proponent of networks as a means of diffusing power. I believe that Hayek in his time understood the nuanced dynamics of coercion, and his effort to increase human freedom through promoting networked forms of decision making was genuine. I also believe that we can learn a lot about collectivity from studying beehives, ant colonies, and insect swarms. However, when it comes to individual agency, humans possess some unique abilities.

Developmental psychologists and evolutionary anthropologists have shown that humans are unique in their capacity for shared intentionality or joint agency: the ability to participate with others in collaborative activities with shared future goals and intentions, not despite of but exactly because of their capacity for individual reflection.

Humans can adapt their collaborative strategies, innovate, and find novel solutions to new problems through separating the ‘I’ from the ‘we’. Insect coordination, while incredibly efficient for specific tasks (e.g., building structures, finding food), operates within the constraints of predefined behavioural repertoires and has very little ability for innovation.

III.

There is something uniquely human about the ability to deliberately change the conditions under which new problems emerge, instead of merely solving them.

Humans can not only act upon the world through their day-to-day actions, but also create new worlds by deciding to become new kinds of actors. For example, if I decide to become a scientist, a better daughter, or a musician, I can realise this through a sort of a meta intentionality that will guide my ground-level actions that will cumulatively result in me becoming a new type of actor. And once I change into this new type of actor, the meta intentionality disappears and my day-to-day decisions become that of a scientist, good daughter or musician. Thus, human agency exhibits a hierarchical structure: initially based on ground-level day-to-day choices and subsequently on the world-level perspective that keeps us striving for becoming new types of actors.

This concept of becoming a new kind of decider is expounded by neuroscientist Peter Ulrich Tse in his book 'The Neural Basis of Free Will'. Tse suggests that humans possess a unique ability to evaluate and modify not only their every-day decisions but also the criteria based on which their decisions are made. What is most remarkable in this phenomenon is that it is akin to how individual neurons fire in our brains. Contrary to the popular notion of firing in an on-and-off switch manner based on stimuli, neurons do something more: they reparameterize the constraints and choose the criteria by which they allow themselves to be affected.

Tse argues that this behaviour of the neuronal code implies a different type of causality, one that complements interventionist causality, the dominant interpretation of causality where if A causes B, B follows passively from A. In the version of causality that neurons seem to be operating by, A causes B only if B “says so,” by virtue of B’s criteria having been met. This criterial causation is, according to Tse, one of the main differences between how causality works in living organisms and nonliving physical systems and might be the key to how life emerged from non-life on earth.

Once causation by reparameterization came not only to involve conditions placed on physical parameters (e.g., molecular shape of a neuro- transmitter before an ion channel would open in a cell membrane), but also conditions placed on informational parameters (fire above or below baseline firing rate if and only if the criteria for a face are met in the input) that were realised in physical parameters (fire if and only if the criteria on the simultaneity of spike inputs are met), we witnessed a further revolution in natural causation. This was the revolutionary emergence of mind and informational causation in the universe, as far as we know, uniquely on Earth, and perhaps for the first time in the history of the universe.

- Tse, Peter U., 'Two Types of Libertarian Free Will Are Realized in the Human Brain', in Gregg Caruso, and Owen Flanagan (eds), Neuroexistentialism: Meaning, Morals, and Purpose in the Age of Neuroscience

These two types of causality (criterial and interventionist) can be interrogated through the two levels of reality that philosophers distinguish as ontic and ontological. The ontic level refers to the factual state of affairs or phenomena, as they are empirically or experientially given. It is the data, the materially existent, and the discrete elements that can be observed, interacted with, or measured through empirical research. In contrast, the ontological level means the conditions or criteria that govern the ontic level.

To use an analogy from software development, the ontic level pertains to the code that runs, the functionalities it offers, and the interactions it facilitates; while the programming framework would map onto the ontological level: the principles of how components interact, the possibilities and limitations of the application’s architecture, and the underlying logic that enables the software's functionalities.

Empirical research is primarily concerned with the ontic level of reality. It focuses on observing, measuring, and analysing specific phenomena. On the other hand, speculation, unique to exploratory research, acts on the ontological level. It involves contemplation about the fundamental structures that underpin the ontic level, venturing beyond the immediately observable, seeking to explore the 'unknown unknowns' that account for the deeper, more abstract principles governing the ontic. This mode of inquiry is crucial for creating new concepts that can later be tested by empirical experimentation.

Critique, or reflexivity, operates on both the ontic and ontological levels, providing a reflective examination of empirical findings, speculative ideas, and the methodologies by which these insights are obtained. The interplay among empirical research, speculative inquiry, and reflexive critique form a framework that is indispensable in times of revolutionary technology.

To borrow and slightly reframe another analogy from Peter Ulric Tse: a scientist studying the size, weight, and momentum of a ball only through empirical methods would never be able to understand why the ball never touches the hands of the football player, only their feet. The rules and social significance of football would only reveal themselves if the scientist applied speculation to understand what a game is, and critique to understand it’s role in identity formation, community cohesion, national pride, and international diplomacy. And if, under times of revolutionary football, the notion of the ball game is being redefined, adopting methods that will allow us to shape the concept of a “game” is essential.

What I’m trying to convey with all of this is, if we wish to “keep our hands on the wheel” in times of revolutionary technological change, we need to move beyond the incremental optimization-based product development frameworks widely adopted and in use currently in the tech industry. Because the industry is no longer only exploiting validated hypotheses from academia, we must adopt practices that for centuries enabled scientists to do research that shape the concepts we live by.

IV.

Progress implies there’s a pre-defined future we’re all marching forward, a pursuit of novelty accepts that the only constant is change.

Raised in an environment that instilled a deep-seated cynicism in me toward anything posing as progress, I've become quite resistant to coercion by the swarm. Being a Hungarian minority in '90s Serbia meant navigating the tension between my lack of agency due to the socioeconomic and political situation (the aftermath of the Yugoslav Wars) and the allure of a way of life depicted in Western media. This resulted in a very weird notion of agency. I was always very curious, but coupled with a constant urge to become invisible, at times feeling like I wanted to disappear entirely, at others dreading it. Whenever I was asked what I was going to be when I grew up, I answered obediently—a vet, a computer scientist, an artist—but I never really mean it; I really was just playing a language game. Even though I had the freedom to choose what to eat for breakfast or what to wear for the day, this was a very superficial type of freedom—one that only allowed me to think about my immediate future, but limited me in pondering what kind of actor I wanted to become later in life.

I still vividly remember the rush I felt hearing the sound of the 56k dial-up modem when the local IT guy set up my internet for the first time. At the age of 10, that sound literally meant the world to me. It exemplified a bridge to a type of freedom I knew so well from Hollywood movies. The internet opened doors to endless possibilities, granting access to a world brimming with knowledge. In contrast, video games were quests for wonder, an exploration of novelty, where each game was a portal to entirely new universes with their own rules and limitations. I was never really interested in following the game designers’ pre-defined paths, but rather, I wanted to discover new ways of playing the game, seeing what worlds would be revealed to me if I pushed the limits of the possible.

I don’t think technology is merely a utilitarian force treating everything as resources to be measured, ordered, and controlled. Stemming from something deeper, more primal, preceding regimes of resource management, it is in direct relation to how life itself creates boundaries in order to perpetuate itself. Ultimately revealing instead of capturing—a constructive process that through enframing the unknown, creates new conditions for creative genesis, making life richer in content and form.

I also believe that we have a moral obligation not to blindly submit ourselves to runaway forces whose only purpose is the perpetuation of themselves. Otherwise, what is the point of having the ability to collectively shape new worlds, literally just through deciding to believe in them. And if that is the case, why not shape the collective imaginary with more deliberation? Why not revel in the aesthetic acts of exploration, wonder, and innovation instead of submitting ourselves to ideologies that advocate for acceleration without imagination?

Dissolving oneself in the collective is a beautiful feeling, but if there's no individuality left to nourish the collective with, one disappears without making a difference. And those of us privileged enough to be in a position to make a difference should not squander that privilege.

If you made it till here, thank you! <3 Please feel free to comment or reach out if this series of provocations resonated with you.

This was really great! Good insight from inside the machine. And really interesting to hear about your background and how it shaped your thinking.